Authors: Jitka Stilund Hansen, Thomas Kaarsted, Simon Worthington, Paul Ayris, Bastian Greshake Tzovaras, Kirsty Wallis

Citizen Science Skilling for Library Staff, Researchers, and the Public

Section Editor Jitka Stilund Hansen

v1.0

Series: Citizen Science for Research Libraries — A Guide

DOI: 10.25815/hf0m-2a57

Increasing Scientific Literacy with Citizen Science

Citizen science has the potential to sustain the citizen in developing scientific skills and to increase public understanding of science. Thus, scientific literacy can be an integral part of citizen science projects.

By Berit Elisabeth Alving, University of Southern Denmark,

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-4708-5000 e-mail: balving@bib.sdu.dk Article DOI: 10.20389/dnnk-tv30

Scientific literacy and citizen science

Citizens who are scientific literate can contribute and collect data in a useful and qualified way in e.g., citizen science projects and can to a greater extent use scientific methods and make informed decisions. Some citizen science projects can even increase the participants’ scientific literacy, if projects may contain elements of empowerment, inclusion, and motivation. For citizens to acquire knowledge and thus, become more literate, the citizen science projects must be relevant and preferably related to the citizens’ local environment. Personal involvement and interests makes people more motivated, and thus more likely to seek information. Effects of citizen science projects on scientific literacy could be better comprehension of scientific information and scientific processes and a change in attitudes towards science. The citizens may engage more in science or even consider science as a career.

Research libraries and scientific literacy

The libraries’ mission to promote and provide tools and resources to master scientific information and information literacy, even scientific literacy, matches the citizen science projects, where citizens acquire scientific skills in observing, deriving, predicting, and making sense of collected data and observations. By connecting scientific researchers with scientific literate citizens, the library could become a channel for citizen science projects, as well as an intellectual hub. The library will be a place to access and use scientific information as well as to create and engage in scientific endeavours.

The University Library of Southern Denmark is a partner of citizen science projects and several of these involve pupils from elementary schools and high schools. In one project, “A Healthier Southern Denmark”, high school classes were involved and learned about health science and the library held a course in critical source reading as a supplement to the students’ curriculum. Another example from the university library is the project “Find a lake”, where elementary school pupils test the quality of the water. The latter had a goal to educate the pupils to be responsible citizens through insight on humans’ impact on nature. The pupils were highly motivated and the purpose of the projects was clear and relevant to them. Both projects and the educational material were a co-creation between the schools, the researchers, and the university library. The library acted as a link between the schools and the researchers.

References

Golumbic, Yaela N., Barak Fishbain, and Ayelet Baram-Tsabari. “Science Literacy in Action: Understanding Scientific Data Presented in a Citizen Science Platform by Non-Expert Adults.” International Journal of Science Education, Part B 10, no. 3 (July 2, 2020): 232–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/21548455.2020.1769877.

Shaffer, Justin F., Julie Ferguson, and Kameryn Denaro. “Use of the Test of Scientific Literacy Skills Reveals That Fundamental Literacy Is an Important Contributor to Scientific Literacy.” Edited by Peggy Brickman. CBE—Life Sciences Education 18, no. 3 (September 2019): ar31. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.18-12-0238.

Definition of Scientific Literacy

Scientific literacy is knowledge and understanding of scientific concepts, processes, and methods, giving you the ability to discuss and evaluate the origin and quality of scientific results and thus seek answers to scientific questions. The scientific literate citizen can distinguish science from pseudoscience.

Examples on measuring scientific literacy

To detect the citizens’ level of scientific literacy, it is useful to conduct a test at the beginning and end of a project, and thereby be able to evaluate the progression in scientific literacy. These tests are specifically useful when schools or educational institutions are involved. The citizen science projects can be part of or a supplement of their curriculum. Below are examples from the Test of Scientific Literacy Skills (TOSLS) used for undergraduate students. In this test, they must organise, analyse, and interpret quantitative data and scientific information.

- Which of the following is a valid scientific argument?

- Measurements of sea level on the Gulf Coast taken this year are lower than normal; the average monthly measurements were almost 0.1 cm lower than normal in some areas. These facts prove that sea level rise is not a problem.

- A strain of mice was genetically engineered to lack a certain gene, and the mice were unable to reproduce. Introduction of the gene back into the mutant mice restored their ability to reproduce. These facts indicate that the gene is essential for mouse reproduction.

- A poll revealed that 34% of Americans believe that dinosaurs and early humans co-existed because fossil footprints of each species were found in the same location. This widespread belief is appropriate evidence to support the claim that humans did not evolve from ape ancestors.

- This winter, the northeastern US received record amounts of snowfall, and the average monthly temperatures were more than 2°F lower than normal in some areas. These facts indicate that climate change is occurring.

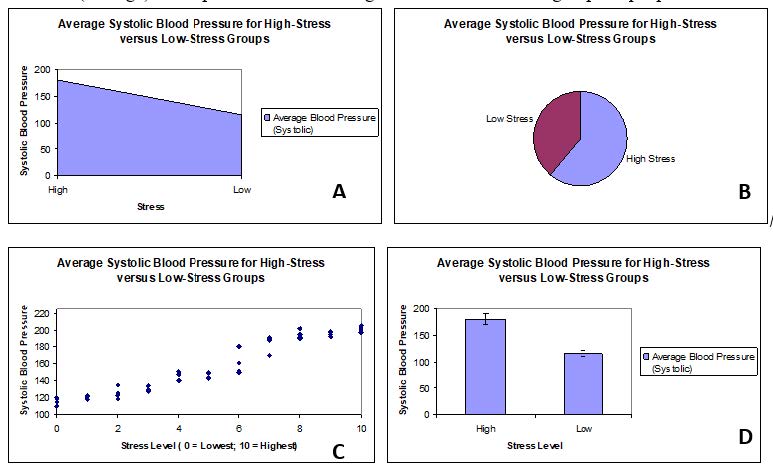

- Researchers found that chronically stressed individuals have significantly higher blood pressure compared to individuals with little stress. Which graph would be most appropriate for displaying the mean (average) blood pressure scores for high-stress and low-stress groups of people?

Note

Examples reprinted with permission from publisher and author: Gormally, Cara, Peggy Brickman, and Mary Lutz. “Developing a Test of Scientific Literacy Skills (TOSLS): Measuring Undergraduates’ Evaluation of Scientific Information and Arguments.” Edited by Elisa Stone. CBE—Life Sciences Education 11, no. 4 (December 2012): 364–77. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.12-03-0026.

User Type

- Citizen scientist/civil society organization

- Educator/museum

- Researcher/research institution

- Teacher/school

Resource type

- Case studies

- Getting started

- Step by step guides

Research Field