Authors: Carina Veeckman [VUB], Floor Keersmaekers [VUB], Karel Verbrugge [VUB], Eline Livémont [VUB]

Veeckman, C., Keersmaekers, F., Verbrugge, K., & Livémont, E. (2022). D3.3 Citizen Science Starters Kit (Online Citizen Science Training Materials) (Version 2). Zenodo.

Determine if citizen science is right for your research

Before you choose a citizen science approach, it is recommended that you reflect on whether it is the right method for your research (project). Citizen science does not fit for all research topics. In certain circumstances, more conventional science methods or other types of public engagement mechanisms might just do the trick or might be even better suited.

This module helps you to reflect and determine whether citizen science is the right method for your research (project). Several situations are described which lead to beneficial outcomes, with helpful examples in the various scientific disciplines.

Goal: At the end of the module, you are able to assess whether citizen science is suitable for your research (project) and decide on the right type of citizen science research. The different types of citizen science approaches are explained at the end of the module.

When is a citizen science approach appropriate?

Citizen science may yield many benefits, both scientifically and socially. However, when you are new to citizen science it is hard to decide whether it is the right approach for your research objectives. In the right circumstances, citizen science may be very beneficial. In other circumstances, other ways to engage the public may be more appropriate.

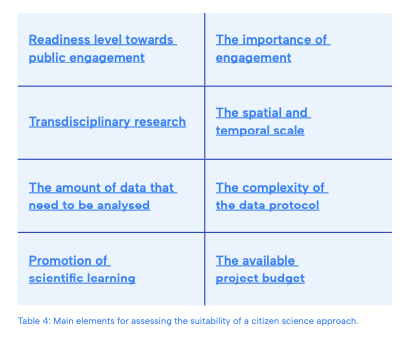

In this chapter, several decision-making factors are described to help you decide whether citizen science is a viable option. Before you start your project, we advise you to reflect upon the following elements in order to make a well-founded decision:

Readiness level towards public engagement

Nowadays, there is a trend in academia to invest in public engagement mechanisms. More and more projects are getting support for not only opening up research results to society, but also for genuinely engaging the public in research projects. However, little research has been performed on understanding potential organisational shifts within academic culture regarding public engagement. What are the attitudes towards pursuing public engagement in the university, in specific departments and of individual researchers? Is it practically achievable, and which processes need to change to support it? Which capacities are needed, what are potential obstacles?

Applying citizen science might require a change in working habits, operational processes, and in hierarchies. The extent of this necessity is dependent on the type of citizen science project you are going to implement (cf. Typologies of citizen science projects). Furthermore, different challenges might be encountered than those in more conventional scientific methods. Specific obstacles regarding the design and organisation of the project might be experienced (e.g. the mobilisation of participants and sustaining engagement) but there are also data-related challenges (e.g. data quality).

Therefore, before you start with citizen science, take a step back to reflect: “What is your mindset towards public participation in it?” To help you assess your readiness level, you can fill in our readiness test.

If the tests reveal that you need further support for applying a citizen science approach, then the Citizen Science Contact Point can help you. Look out for our various series of workshops and specific one-to-one support services.

Summary

Certain attitudes and new working practices will most probably have to come into place when practising citizen science. Before you consider citizen science, it is advised that you self-reflect on your readiness level. To what extent can you be transparent, open and deliberative about your research? Which capacities are needed to perform the research? Fill in the readiness test and feel free to contact the Citizen Science Contact Point if you need further support on this.

Reading tips:

- This literature review by Weingart et al. describes the main trends on public engagement, and how it shifted from ‘public understanding of science’ to ‘public engagement with science’.

- Have you already heard about the term ‘RRI’? RRI, or Responsible Research and Innovation, is a policy driven discourse that emerged from the European Commission. It aims to foster the design of inclusive and sustainable research and innovation, with an emphasis on co-creation. If you would like to learn more about this discourse, you can read this handbook.

- The Eurobarometer of May 2021 questioned citizens’ opinions on inclusion in science and technology. The study revealed that six out of ten think that involving non-scientists in research ensures that science and technology will better respond to the needs, values and expectations of society.

- Citizen science is one of the eight ambitions of the EU’s Open Science policy. The aim is to engage and involve citizens and civil society organisations in co design and co-creation processes so as to promote responsible research and innovation.

- Read a qualitative study performed in the UK about a shift in attitudes on public engagement in health research here.

The importance of engagement

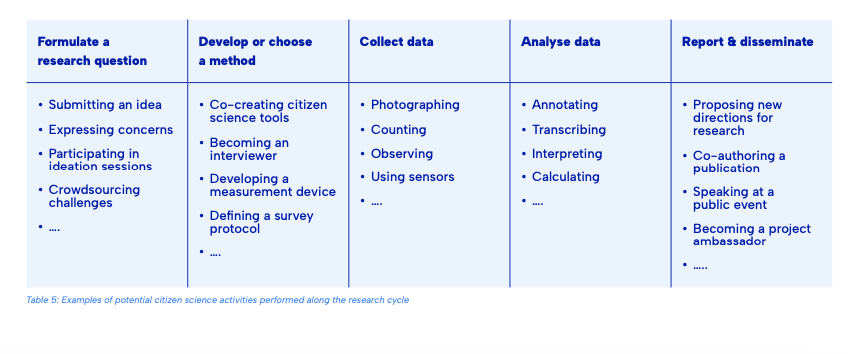

In addition to your readiness level, you should also consider how important engagement is for your research (project) and how you can bring it into practice. Participants can be engaged in the different phases of the research cycle. The table below illustrates a few potential tasks that can be performed by participants, grouped per research phase:

Apart from activities in the scientific research process, citizens can also fulfil tasks related to the research design and project management, such as developing training materials, establishing a network of participants, organizing communication and support mechanisms, holding meetings and events, etc. This is often the case in research (projects) with a high level of citizen involvement (cf. Typologies of citizen science projects).

Regardless of the activity participants are performing, they should be engaged in an active, meaningful way. They are involved in the research as co-designers and implementers of research tasks, and not as a research object. Participants are also no longer the target of science communication, but actively engage in the scientific process. As such, research in which citizens participate as respondents in tests or interviews, complete surveys or attend focus groups is not called citizen science. Rather, when citizens are taking an active role in organizing or conducting these tests, interviews, surveys or focus groups, then we do call it citizen science.

Citizen science should not be confused with participation. Many participatory projects actively involve citizens in policy, innovation and other topics. The co-creative methods used in these projects can also be applied in citizen science. However, if these methods do not provide data from which scientific conclusions can be drawn, it is not citizen science. For instance, if these methods are more focused on informing about a particular issue, then we speak of science communication.

If we take these two elements into account, i.e. active, meaningful engagement and participation for purposeful scientific research, it may well be that citizen science does not f it your problem statement. In that case, more conventional methods might be better suited.

Reading tips:

- If you would like to learn more about engagement strategies and tools, you can consult this practical guide to communication and engagement in citizen science.

- From a theoretical perspective, science communication models and theories lie on a spectrum from more scientific-oriented to public-centred. You can read more about the deficit model, the dialogue model and the participatory model (of which citizen science is an example) in this publication.

- This publication outlines different models and impacts of public participation in scientific research and discusses it from the perspective of different fields and traditions.

Time to reflect – share your thoughts and opinions:

- What is the importance of citizen engagement in your research (project)?

- Which type of activities can citizens perform?

- Do you think that one-way communication might be sufficient for your research?

- Do you think you can get more out of your research if you encourage people to contribute to certain research activities?

- Do you think your research would be possible without the contribution of citizens? If yes, what is the added value of the citizen science approach?

Transdisciplinary research

Citizen science is highly suited to creating transdisciplinary connections by constituting a research team from different scientific disciplines and different faculties. Interdisciplinary environments challenge researchers to work together to reach a common goal, to find a common vocabulary and share knowledge. At the European level, Research & Development programmes are calling for higher interdisciplinarity to come up with quicker and more effective solutions to wicked problems.

Furthermore, citizen science is also highly suitable for collaboration with stakeholders from outside academia. In citizen science projects, we often see collaboration among the following actors:

- Civil society: citizens, action groups, civic associations, and other (voluntary) societies where participants can be recruited through a membership base

- Knowledge institutions: research and science institutions, schools, (vocational) universities and educational associations (science museums, libraries)

- Governments: towns and cities, authorities on the local level and other public organisations • Industry: private companies with expertise in types of sensors, building platforms, legal or judicial advice, communication and media for instance

- Funders: Local, national or European institutions that provide funding or launch grant calls for citizen science

By stimulating transdisciplinary dialogue, citizen science can help in facilitating a shared understanding among stakeholders and the research team. It can also help in making the research more locally relevant, and in providing a holistic perspective of the issues at hand.

Reading tips:

- Read more about transdisciplinary research here, written by Christian Pohl (2011).

- The social sciences and humanities (SSH) are gaining more acknowledgement within interdisciplinary citizen science projects. This discipline helps to learn about the social dimensions of the research, and to provide a framework for engagement. Read more about the inclusion of SSH in this article from Tauginienė et al. (2020).

- This article from Hidalgo et al. (2021) stresses the communicative and dialogical translation work that is required in interdisciplinary teams.

- You can read more about how to set up collaborations and partnerships with local government in Chapter 5 of the handbook ‘Citizen Science roadmap for local government’, developed by Scivil (in Dutch).

The spatial and temporal scale

Citizen science is highly suitable if you need to collect or analyse data across large spatial scales and/or over longer periods of time. It is one of the main reasons why people decide to perform citizen science: teamwork makes the dream work. By engaging a large group of citizen scientists at the same time, the research can be more effectively accomplished. The time and costs needed for the same job performed by more conventional science methods would be considerably greater.

For this reason, we see many citizen science projects in the field of environmental monitoring. Citizen science allows to collect data at a fast pace, and at places that otherwise would not have been accessible (e.g. in private gardens, or at remote locations). Since many of these projects are repeated over time, it also allows species and ecosystem dynamics related to environmental changes to be studied. In some cases, the citizen science monitoring programmes are even able to collectively produce finer grained and more expansive datasets than official measurement programmes. In this regard, debates are currently occurring concerning whether citizen science data is of sufficient quality to use for policymaking.

Tips:

- Official air quality monitoring stations are rather sparse in Flanders (Belgium). Read how the Curious Noses monitoring programme improved the air quality models in Flanders with air quality data on street level thanks to the participation of 20,000 citizens here.

- These applications are used for environmental monitoring purposes with a large spatial and temporal scale: iNaturalist, eBird and Map of Life.

- On national level in Belgium, we have the database https:// waarnemingen.be/ by Natuurpunt and Natagora for observations in nature. For monitoring the weather, there is the database of WOW-BE (Weather Observations in Belgium)

The amount of data that need to be analysed

Citizen science is also highly suitable when large amounts of data need to be analysed. For instance, when you need to analyse a large historical database with manuscripts, satellite images, or webcam photos. If you can make these data available, citizen scientists can help in speeding up the analysis process.

For processing large volumes of data, we often turn to computers to help us out. However, in some cases human ability is still superior. Humans are still delivering better results for sorting tasks, pattern recognition and analysing audio and images. In this regard, citizen science is meeting artificial intelligence nowadays. Citizen scientists are helping to train deep learning algorithms based on the classifications performed. Once fully trained, the software applications will carry out automated classifications. Online platforms that can help you with the analysis process are The Zooniverse Platform, doedat.be and velehanden.nl.

Be aware that for processing large volumes of data, the motivation of participants might decrease when tasks are dull and very repetitive in nature. In this regard, gamification and fun elements can help. For instance, the Zooniverse platform offers a space to save, share and discuss objects users have found. Users can post in the ‘Talk picture’ sharing function and discuss examples that could be mistaken for artwork. Other potential game elements are badges, listing top contributors of the week, unlocking levels, group missions, etc. These elements work very well for younger age groups and extrinsically-driven participants.

Case study: The Zooniverse platform

The Zooniverse is the world’s largest and most popular citizen science platform for data analysis. Around 1.6 million users are registered who are contributing to research projects in all scientific disciplines. With the help of the volunteers, researchers can analyse their information more quickly and accurately than would otherwise be possible. Via the Zooniverse builder you can create your own powerful interface for data analysis.

More information: https://www.zooniverse.org/

Lastly, if a large amount of data needs to be analysed, you also need to reflect on the complexity of the protocol. For analysing a large amount of data, you will hope to engage large numbers of citizens who are able to finish the task in a fast and simple way.

The complexity of the data protocol

The complexity of the data protocol can is another decision making factor. The data protocol is the way participants are going to collect data in your project. The main rule of thumb is to keep this as easy as possible. The easier participants can collect data, the more likely you will collect data of high quality. If the data protocol is too difficult, participants might drop out quickly, you might exclude certain groups, or end up with inaccurate data measurements.

Case study: The data protocol of the Eye for Diabetes project.

The Eye for Diabetes project engaged citizen scientists for annotating retinal images in order to train an algorithm for early disease detection of diabetic retinopathy. In this project, the Zooniverse platform was used to annotate a dataset of retinal images. Participants had to surf to the Zooniverse portal, where they had to register in order to keep a record of their contributions. A short tutorial explained them how to complete the tasks. Participants were first introduced to simple tasks and, over time, they progressed to more advanced tasks. Overall, it was decided that each image should be annotated by at least ten different participants in order to identify outliers.

Website: https://www.oogvoordiabetes.be/

A straightforward protocol will also help you to engage a large audience. If a lot of data need to be collected or analysed, it is recommended that participants can follow a standardised approach. The protocol should ensure, to the extent possible, that participants are able to collect or analyse the data independently. This is certainly the case when participants collect data at private or dispersed locations.

More complex protocols are also possible in citizen science projects. However, you need to be aware that only a particular type of profile, most often with an expert background, can participate (e.g. naturalists, hobbyists, medical professions, etc.).

How-to guides and/or training sessions can support citizens in learning how to apply the protocol. It often helps when the protocol is explained in small and simple tasks. Furthermore, a test session can be organised with friendly users to evaluate the quality of the protocol. These insights can help you to ameliorate the comprehensibility of the task descriptions, and to check the consistency of the data. Test sessions can also help to build in extra validation options in order to ensure that the data is correctly collected or analysed.

Tips:

- Be aware that certain groups might be excluded based on the design choices of your data protocol. Not everyone has access to the Internet or a smartphone or has the appropriate digital skills for your project. If you would like to make your project accessible to everyone, be sure to provide an alternative with the right support.

- Get to know your participating citizens and match their skills and knowledge with your data protocol. For instance, to what extent are citizens familiar with using sensors? Do they have previous experience with annotating images? Small tasks can be outlined for beginners, while more experienced citizens can follow more advanced protocols. Over time, beginners can level up to more advanced tasks.

Further reading:

- This guidebook from Pocock et al. (2014) includes a decision framework for citizen science in the field of biomonitoring, and includes several questions on the data protocol.

- The data charter for citizen science (available in Dutch and English) can help you with further questions on data quality. This data charter is published by Scivil, the Flemish Knowledge Centre on Citizen Science, in collaboration with Digitaal Vlaanderen.

- The online MOOC of the WeObserve project teaches you to capture and analyse data and use the findings to take action. The MOOC is particularly relevant for citizen science projects and citizen observatories focusing on environmental monitoring.

Promotion of scientific learning

If you would like to bring science to the classroom, you can choose to set up a citizen science project. Through citizen science, pupils and students can take part in science through fun and hands-on activities. In these projects, researchers and school/student communities are working in tandem. On the one hand, observations can be collected that advance real science and, on the other hand, curiosity and learning are sparked.

Engaging youngsters, students and teachers in a citizen science project can help to promote scientific literacy. Pupils and students can connect with scientific knowledge and be inspired about the work of scientists. They learn how to ask scientific questions, run experiments and can draw evidence-based solutions. Researchers can also train teachers in scientific inquiry and research methodologies. This ensures that the activities are meaningful for all, and that teachers can support the activities to guarantee good quality data.

Different citizen science approaches for promoting scientific learning can be applied. Firstly, you can choose to design your project specifically for school education, whereby the pupils or students are invited to participate as part of their school curriculum. In specific cases, citizen science also has the potential to activate Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) learning. A second approach is that you extend the scope of your project with (in)formal education and classroom practices, by developing specific information packages. Formal learning generally occurs in the classroom with clear learning objectives, whereas informal learning takes place outside the classroom, or after school, in places like museums nature clubs, fablabs, etc.

If you would like to implement citizen science in formal education, then the following tips can help you:

- Decide in advance which age group is suited to your project

- Define the learning objectives and attainment levels and mention these specifically in your communication to the teachers. With this information, they can determine whether your project fits their lessons

- Adapt your activities to the school context (take into account holidays, school hours, …)

- If possible, collaborate and co-design the materials together with a teacher, or consult a teacher from time to time about your approach so that it can be well aligned with the classroom context

Further reading:

- Scivil provides a handbook on ‘Citizen science in the classroom’. You can consult it as a pdf or through the online e-class.

- If you would like to read more about citizen science in the classroom, you can check the materials developed by the BRITEC project. They offer different guidebooks and also a MOOC on citizen science education.

- This article from Roche et al. (2020) talks about the challenges and opportunities of citizen science projects in formal and informal learning environments.

- There is a European Citizen Science Association (ECSA) working group on learning and education in citizen science, which helps to develop the informal learning and educational aspects in citizen science projects. Learn more about this working group here or read their book chapter with main highlights here.

- You can consult this article from Philips et al. (2018) if you would like to measure the individual learning outcomes of your research (project).

The available project budget

Citizen science can be a cost-effective way to gather a vast amount of data in a short period of time. With the help of citizen scientists, scientific information can be collected on scales and at resolutions that would have not been possible for individual researchers or whole research teams. It is however a misunderstanding that a citizen science project is free of charge. There are several costs, different to regular research projects, that you need to consider.

Firstly, there are personnel costs related to the recruitment and engagement of citizen scientists. Participants should be looked for, engaged and motivated to remain in the project. Time should also be allocated to the training of participants. Trainings can be organised in person or online, with supervision also during the data collection. Trainings and the establishment of a data protocol are vital for ensuring data quality. Personnel costs will also be dedicated to communication and awareness raising activities. Communication is a vital aspect in a citizen science project. Ideally, your project has a science communicator who makes sure that messages, research results included, are communicated in an accessible and understandable manner.

Furthermore, there are material costs, but this does not always have to be the case. Material costs can be very diverse, ranging from measurement kits to a project website. These costs can be limited if the project can rely on open-source materials.

These types of costs can be a potential burden if you want to start with a project. There is a potential risk of not being able to recruit enough participants, in keeping them motivated, or in having sufficient materials. Furthermore, if the budget is limited or only short term, you also run the risk that your research project will be discontinued quickly after its ending.

Tips for finding financial resources:

- Look for sponsors or raise funds from a wide audience through crowdfunding.

- Integrate a citizen science approach in proposals of regular funding streams. The granting of subsidies for this type of research is not limited to specific citizen science calls.

- Local governments often do not have subsidy lines for citizen science projects. Instead, localized citizen science initiatives can often rely on support if there is a link with existing grant lines in connected social domains (e.g. mobility, circular economy, health, etc.).

- Participants can cover a portion of the costs. If you are transparent about the costs and if the intrinsic motivation to participate is high, participants are often willing to contribute financially.

- Build a partnership around your project. That way, not only the efforts but also the costs can be shared.

- Save costs by using open-source software and freely available applications. Developing equipment by yourself is very time-consuming and costly.

Time to reflect – share your thoughts and opinions:

- This article from Scivil outlines seven successful strategies when applying for citizen science funding. What is your experience this far in applying for citizen science funding?

-

How will you guarantee that research involving citizen scientists does not discontinue quickly after the project ending?

Further reading:

- This thesis of Fauver (2016) researches the cost savings of citizen science projects by comparing three projects with their professional equivalent.

- This article from Alfonso et al. (2022) examines the value of citizen-generated data, with a methodology to compare the value with existing environmental observations and the evolution of their costs in time.

- This article from Encarnação et al. (2021) presents the costs incurred for monitoring marine invasive species. It is presented as a low-cost monitoring campaign, for which the strategy can be easily replicated.

- This opinion piece by Dr. Paul Drachman is about economic considerations of citizen science projects. The attention paid to economic factors in citizen science is not particularly high, or not the decisive factor, in comparison with other values such as education and the scientific significance of the project.

Typologies of citizen science projects

Once you have decided that citizen science is the right approach for your research, the next step is to reflect upon the type of citizen science project. In scientific literature, there are several typologies which classify citizen science projects. We discuss typologies based on the degree of participation and the primary project goal.

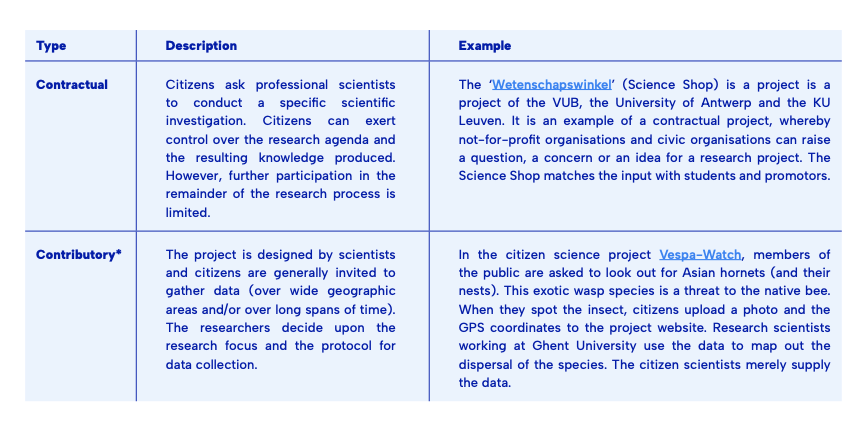

The degree of participation

The most commonly used typology by citizen science practitioners is based on the different degrees to which participants are involved in the scientific process. The models below stem from the broader field of Public Participation in Scientific Research (PPSR), which covers different forms of citizen involvement in research.

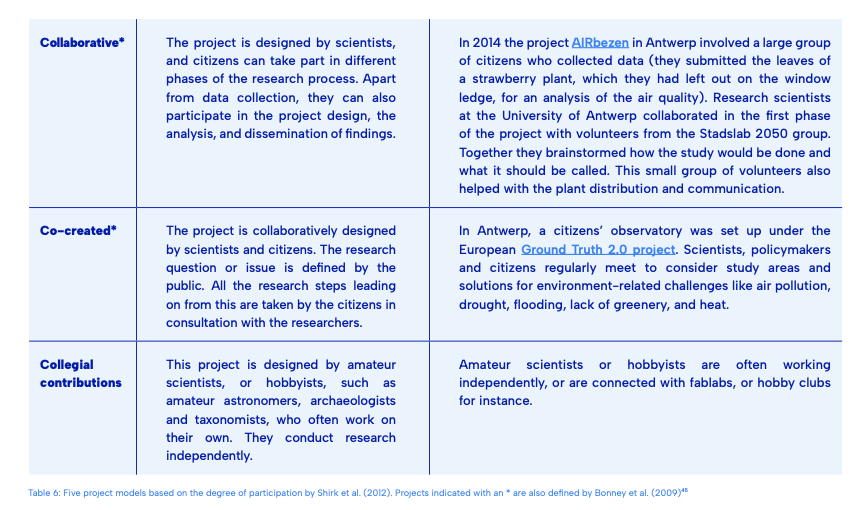

Based on the degree of participation, Shirk et al. categorize projects into five models:

The table above lists the projects from a low to a higher level of engagement, with the contractual and collegial models at the far boundaries of the PPSR spectrum. In the literature, you can find similar models according to the degree of participation but with different labels.

For instance, the typology of Haklay is also commonly used for categorizing citizen science projects based on the level of participation and engagement:

It is important to mention that these typologies are not normative rankings. Not every project needs to engage citizens in every stage of the scientific process. The level of engagement has a lot to do with the research objectives you have in mind. Aspiring to a higher level of engagement is thus not necessary, although it will lead to different types of outcomes for the public. Likewise, engaging citizens more deeply in the research process does not mean that the collected data will be less scientifically interesting.

Tips:

- Think carefully about your research design and choose the type of model with the end goal you have in mind. Will a given degree of citizen participation be sufficient to achieve a desired outcome?

- You do not have to apply one degree of participation in your research (project); you can also facilitate multiple levels. Citizens will inherently create their own individualized experience, regardless of the predominant model of participation in your research. As such, you might have a core group of participating citizens who are engaged in all stages of the research process, while the majority only contributes with data collection or creation.

- You can modify your project design along the project lifetime. This is particularly useful when you notice that your participating citizens are changing their interests and motivations to participate in the research (project). This will support sustained, or continued, citizen participation in the project.

The project goal

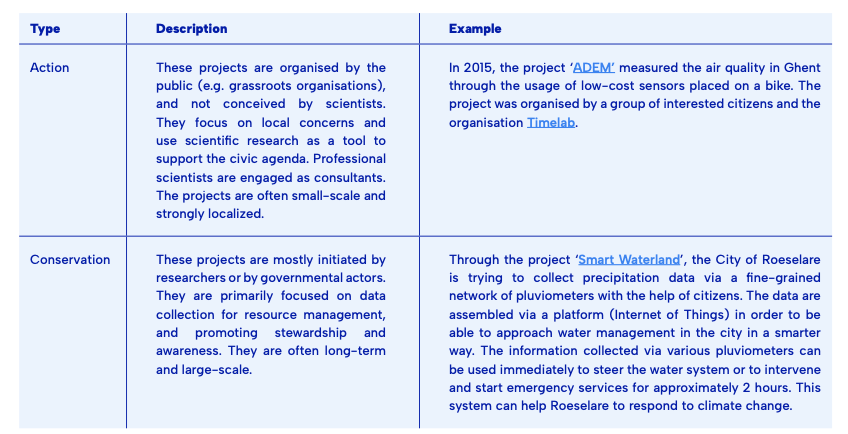

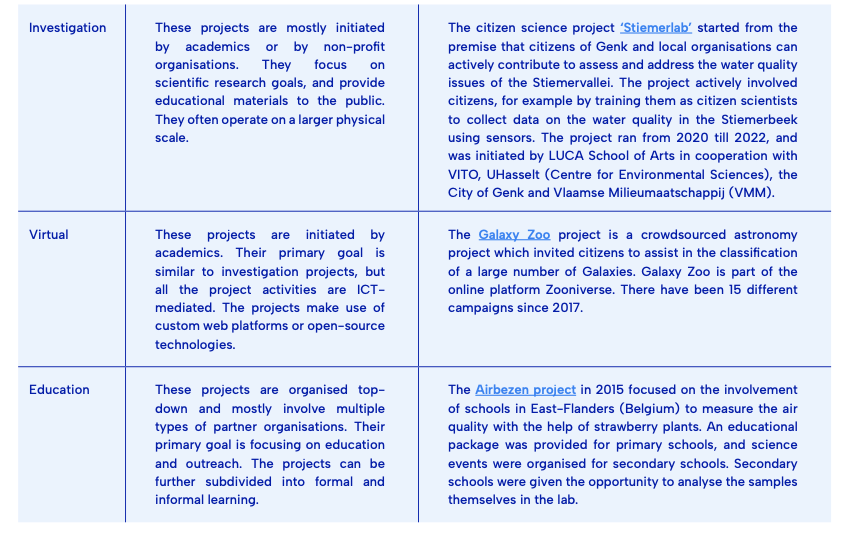

A different way of categorizing citizen science projects is by focusing on the primary target goal of the project. Wiggens and Crowston clustered projects based on the explicit goals mentioned in the project materials, and found five different types of citizen science projects:

Clustering projects based on their goals is to run the risk of thinking simplistically. Many citizen science projects have multiple objectives, often balancing between scientific and educational goals. Projects can originate at the university or at research centres, in the public realm, or both. The taxonomies provided can be useful as a starting point to help you reflect on the type of citizen science research. However, in reality, these taxonomies might blur, with different crossovers in features. Therefore, we recommend reflecting on these typologies as a starting point, from which you then implement the right customized design for your research (project).

Time to reflect – share your thoughts and opinions:

- Which model does your research (project) resemble? What is or are the different degrees of citizen participation?

- If it were feasible, would you set up your research exclusively online? Why (not)?

- Extreme citizen science projects challenge the scientific culture in the sense that it requires scientists to engage deeply with social and ethical aspects of their work. This potential change process is framed by Haklay with the following phrase: ‘the emphasis is not on the citizen as a scientist, but on the scientist as a citizen’. What is your opinion on this?

Further reading:

- Based on the former mentioned typologies of Bonney et al., Shirk et al., and Wiggens and Crowston, this article from Schäfer & Kieslinger (2016) integrates all typologies into one quadrant based on the locus of knowledge creation and the focus of the project activities.

- The typology of van Noordwijk et al. (2021) is focused on distinct participating citizen groups and their motivations to participate. The article describes four different types of projects: place-based community projects, captive learning projects, interest group projects and mass participation projects.

- To further grasp the variety of citizen science inquiries, Fan & Chen (2020) look at it from a political angle and define models related to how citizenship is built into the research (project). Four models are described in their article, namely ‘Cosmopolitan Community knowledge’, ‘Science, State and Citizen’, ‘Democracy and Justice’ and the fourth type ‘Civic commons and techno-social infrastructures’.

User Type

- Researcher/research institution

- Teacher/school

Resource type

- Case studies

- Getting started

- Step by step guides

Research Field