Authors: Carina Veeckman [VUB], Floor Keersmaekers [VUB], Karel Verbrugge [VUB], Eline Livémont [VUB]

Veeckman, C., Keersmaekers, F., Verbrugge, K., & Livémont, E. (2022). D3.3 Citizen Science Starters Kit (Online Citizen Science Training Materials) (Version 2). Zenodo.

The first module of this training kit reflects on the different definitions of citizen science found in literature, as well as its main characteristics. To elucidate what citizen science is (not), practical examples are given throughout the module.

Furthermore, the benefits of citizen science are listed, both for science and society. At the end of the module, the diversity of citizen science is described through practical case studies in various scientific branches and disciplines.

Goal: At the end of this module, you are able to define the main characteristics of citizen science and have a basic understanding about what citizen science is (not).

What is citizen science?

Citizen science, also known as community science, crowd science, civic science, crowdsourcing, volunteer monitoring, volunteered geographic information, is often used as an umbrella term to describe a wide range of participatory activities that involve lay people (‘citizens’) in the scientific process.

In the last decades, societal and technological changes have increasingly allowed citizens to contribute to science, leading to a rapid growth of citizen science in all scientific branches and disciplines. Furthermore, citizen science is also receiving increasing attention from policymakers who are launching specific funding programmes on the local, national and international levels.

The increased interest brought along several definitions, with different terms used to refer to citizen science activities. As such, there is not one single exhaustive definition of what citizen science is, nor a set of specific quality criteria. In this training kit and in accordance with the Flemish Knowledge Centre on Citizen Science in Flanders (abbreviated, Scivil), we use the following definition of citizen science:

“Citizen science involves scientific research conducted in whole or in part by non-scientists (citizens), often in collaboration with, or under the guidance of professional scientists.” (Cambridge English Dictionary)

Citizen science thus refers to research conducted (at least in part) by citizen scientists; citizens who contribute to research in their free time. Citizen scientists often – but not always – collaborate with, or are supervised by domain experts, academics or governments.

Scivil – Bringing science and society closely together.

Scivil is the knowledge centre for citizen science in Flanders. Scivil was founded with funding from the Flemish government (Department of Economy, Science and Innovation) in early 2019 to unite, support and inform scientists, citizens, policymakers and organisations about citizen science. Scivil provides workshops and lectures on citizen science and provides advice to current and future citizen science projects. They also develop guidebooks and manuals and set up thematic working groups on citizen science.

More information: https://www.scivil.be/en

The rise of citizen science: a brief history.

The term citizen science has multiple origins. It was first mentioned in the 1990s by Rick Bonney3 (US, ornithologist) and Alan Irwin4 (UK, sociologist). Their perspectives are being presented as two meanings or strands on citizen science. The first strand, from Irwin, stresses the democratic potential of citizen science. It emphasizes the responsibility of science to society, whereby participants can participate in science in a multitude of ways. At the other end of the spectrum is the narrow usage of the term by Bonney, defining citizen science as an approach for cost effective data collection. In this latter perspective, large volume observations are gathered to serve the objectives of the scientific enterprise, rather than the co-creation of knowledge with society.

However, the concept of citizen science is nothing new in the history of scientific research. If we look at the history of modern science, you can also label the first amateur scientists as ‘citizen scientists. Amateur scientists have been performing research in their free time from their living rooms without being part of any formal academic institution, or without being formally recognized as a scientist. For instance, Caroline Herschel discovered in 1786 a comet, named ‘Caroline’, by studying the skies on her own5. Years later, she became the first female scientist in England at the Royal Astronomy Society.

If you would like to read more on the historical background of citizen science, you can access this MOOC, or this resource of the Citizen Science Track project.

In an article by Muki Haklay, who is widely recognized for his work in citizen science, a list of definitions of citizen science is provided. Depending on the context of application, the definitions of citizen science seem to vary. Some of the definitions have an instrumental focus, while other definitions are rather descriptive or have a normative focus. This multiplicity of definitions should not be regarded negatively. It is important that differences are supported, and they are essential for the further development of citizen science. The risk of one single definition is that a variety of activities is excluded, or that certain practices would not fit into the specific field of research anymore.

ECSA characteristics and principles

Amongst the multiplicity of definitions, the European Citizen Science Association (ECSA) provides guidance to practitioners with regard to fundamental principles which are expected of a good citizen science project. ECSA is the central hub for citizen science initiatives in Europe and aims to support the exploration of how citizen science can be understood and practiced. In 2015, the association published the “Ten principles of citizen science”, which cover the commitments between project organisers and participants on handling of data, ethics and open science, level of engagement in science, etc. It is an often cited and used resource for defining and implementing citizen science. To further address the ambiguity in the field, ECSA and partners of the EU-Citizen.Science project have set up a working group which developed a set of characteristics of citizen science (based on the above principles). These characteristics describe the range of activities that can or cannot be included within a citizen science activity. They recommend reading their document in conjunction with the principles since the characteristics provide concrete demonstrations of some of the principles.

10 principles of citizen science

- Citizen science projects actively involve citizens in scientific endeavour that generates new knowledge or understanding. Citizens may act as contributors, collaborators, or as project leader and have a meaningful role in the project.

- Citizen science projects have a genuine science outcome. For example, answering a research question or informing conservation action, management decisions or environmental policy.

- Both the professional scientists and the citizen scientists benefit from taking part. Benefits may include the publication of research outputs, learning opportunities, personal enjoyment, social benefits, satisfaction through contributing to scientific evidence e.g. to address local, national and international issues, and through that, the potential to influence policy.

- Citizen scientists may, if they wish, participate in multiple stages of the scientific process. This may include developing the research question, designing the method, gathering and analysing data, and communicating the results.

- Citizen scientists receive feedback from the project. For example, how their data are being used and what the research, policy or societal outcomes are.

- Citizen scientists are acknowledged in project results and publications.

- Citizen science programmes are evaluated for their scientific output, data quality, participant experience and wider societal or policy impact.

- The leaders of citizen science projects take into consideration legal and ethical issues surrounding copyright, intellectual property, data sharing agreements, confidentiality, attribution, and the environmental impact of any activities.

- Citizen science is considered a research approach like any other, with limitations and biases that should be considered and controlled for. However, unlike traditional research approaches, citizen science provides opportunity for greater public engagement and democratisation of science.

- Citizen science project data and meta-data are made publicly available and where possible, results are published in an open access format. Data sharing may occur during or after the project, unless there are security or privacy concerns that prevent this.

To further explain what citizen science is (not), we clarify some additional aspects which often lead to a misunderstanding:

- Citizen science is not equal to disseminating science information. In citizen science research, the public actively participates in the research and is not merely the target of science communication. The public is actively engaged in the scientific process, whereby science communicators still ensure that the whole process and outcomes are communicated in an accessible way to the participants.

- Citizen science is not equal to science ‘about’ citizens but rather refers to scientific research undertaken ‘with’ or ‘by’ citizens. In some disciplines, such as the medical and social sciences, it is common that citizens themselves, their behaviours, challenges, needs, etc. are under examination. In these disciplines, it is possible that people who take part in such projects can be both subjects and participants at the same time8.

- The term ‘citizen scientist’ does not refer to a scientist whose work is characterized by a sense of responsibility to serve the best interests of the wider community. This definition was used by the New Scientist magazine in 1979 but is nowadays rarely being used.

- Citizen science is not driven by commercial gain. If the main aim of the activity is driven by commercial gains, e.g. being paid for providing data, then it is not considered citizen science.

Further reading:

- ECSA platform https://ecsa.citizen-science.net/ • We recommend exploring the EU-Citizen.Science platform of the European Citizen Science Association (ECSA), where you can find an extensive database of resources about citizen science, as well as the latest projects and updates in the field:

- ECSA resources https://eu-citizen.science/resources

- ECSA projects https://eu-citizen.science/projects

- Research work on ‘Characteristics of Citizen Science’.

- Links towards other trainings and handbook resources:

- Michael Pocock, Daniel Chapman, Lucy Sheppard & Helen Roy, Choosing and Using Citizen Science. (Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, 2014)

- Lisa Pettibone, Katrin Vohland et al., Citizen science for all. A guide for citizen science practitioners. (Buerger schaffen Wissen, 2016)

- John Tweddle, Lucy Robinson, Michael Pocock & Helen Roy, Guide to Citizen Science. Developing, implementing and evaluating citizen science to study biodiversity and the environment in the UK. (UK-EOF, 2012)

Time to reflect – Share your thoughts and opinions:

- One of the most popular citizen science projects in Flanders is Curieuzeneuzen (‘Curious Noses’). With 20,000 participants, it was one of the largest projects organised on air quality. Are you able to demonstrate that this is indeed a citizen science activity by applying the ten principles to this case?

- Two important delineators in the discussion on what citizen science is (not), are the level of engagement within a project and a genuine research outcome. Based on these criteria, can you think of an example of a project which is not defined as citizen science?

- Is this citizen science or not?

-

- On FixMyStreet, citizens can report incidents in public space (trash, damaged sidewalks, broken traffic lights, etc.) to their city or town. Volunteers often upload photos and observations to an application or online platform. Is this citizen science or not?

- The Town-City Monitor is a policy monitor that assesses the broad environment of a city or town using about 300 indicators or sets of figures. More than 100 of these come from a large-scale three- yearly citizen survey. In all 300 Flemish cities and towns, citizens are invited to fill in a questionnaire to evaluate how they experience living in their city or town. Is this citizen science or not?

- Sarah is a social worker. Her work is emotionally demanding and she has discovered that watching birds improves her wellbeing. Being new to birding, she uses a bird observation recording app. It allows her to maintain a list of birds that she observes. Observations are shared as open data and contribute to ornithological research and environmental management.10 Is this citizen science or not?

- Stefano is a high school student. During his visit to the local museum, he spends time at an interactive exhibit that shows him the different mammal species in the area, which were photographed by camera traps. The exhibit invites visitors to identify them, giving a score at the end. It was designed by the museum’s experts and data from interactions is not stored or used beyond session duration and visitor numbers.11 Is this citizen science or not?

- Ella is a web designer and interested in a healthy lifestyle and technology. She uses the TopFit smartwatch to collect biometric data throughout the day to monitor an reach personal health and fitness goals. She shares this data with the TopFit community and sometimes participates in TopFit challenges. She pays a subscription fee and receives personalized dashboards, notifications and tips. She often follows this advice and has changes her routines.12 Is this citizen science or not?

Terminology matters

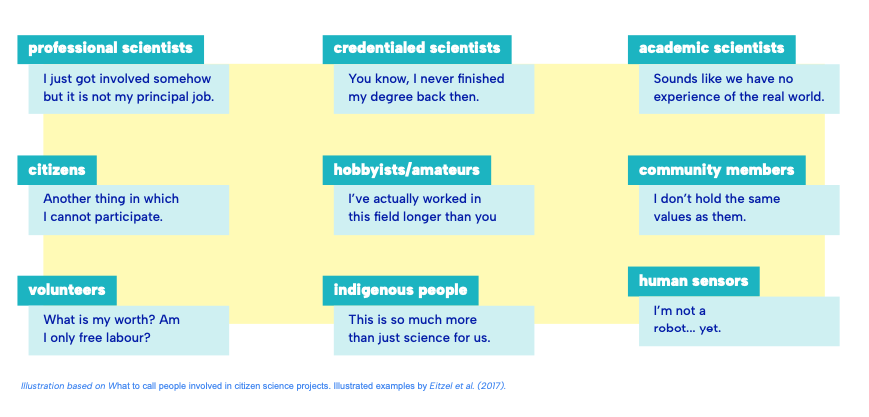

Terminology matters, also in citizen science. The words that we use for what we observe or what we describe can matter greatly for people. Language is a sensitizing concept. Therefore, it is recommended to communicate clearly about the main terminology used, in accordance with the objectives of your research. Explain why you opt for certain terms and discuss how someone feels affected by them. For instance, which terms are you using to describe the citizen science activities, and what do you call people involved in the research?

In this training kit, we opt for the term ‘citizen scientists’ or ‘citizens’ to refer to people who participate in a citizen science project. These may be individuals, groups of citizens, or networks and organisations. On the other hand, we refer to ‘researchers’ as professional scientists who work in academia or in a research-performing organisation who coordinate or participate in a citizen science project as a stakeholder. Activities can also be organised by public bodies (e.g. cities or towns) and non-governmental organisations (e.g. charities).

The below figure, based on an illustration in the article of Eitzel et al. (2017), gives an overview of the commonly used names to describe people who participate in citizen science. Every term is explained and interpreted in a different (negative) way:

Benefits of citizen science

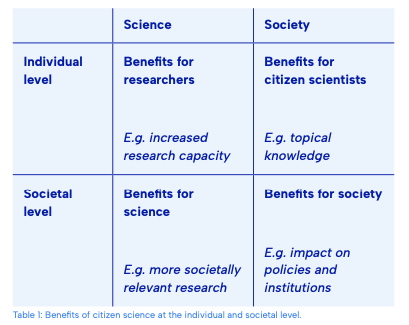

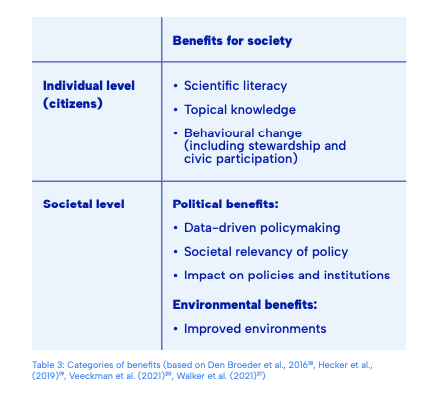

Citizen science can yield a variety of benefits and outcomes. They can occur at the individual level or at the larger science- society level. Individual benefits mainly occur for researchers and citizens, while societal benefits can occur for the broader community, and society as a whole. From the individual participant’s perspective benefits can be related to, for instance, increased topical knowledge, while on societal level this can be related to political and environmental types of benefits.

It is important to note that this typology is not exhaustive and that benefits might be mutually inclusive. Furthermore, the types of benefits that can be generated will largely depend on the objectives and design of your research.

The main benefits for science and society are listed in detail in the following sections, with additional reading tips.

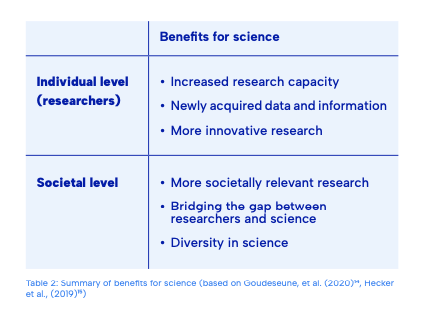

Benefits for science

Citizen science can yield individual benefits and outcomes for researchers in the following ways:

- Increased research capacity: One of the main reasons why researchers opt for citizen science is the increase in research capacity for data collection and analysis. The work done by citizens does not have to be performed by the researchers themselves, and this is particularly interesting when you want to set up a long-term monitoring programme with a large spatial and temporal coverage, or when a vast amount of data needs to be collected or analysed. The main advantage is thus the shared workload, up to the point where (some of) the research would not be able to take place without the tasks performed by the citizen scientists.

- Newly acquired data and info: Through the participation of citizens in your research, you can add lay, local and traditional knowledge to scientific knowledge. Citizen science can thereby not only increase the amount of research data but can also result in more qualitative and diverse data and information that would otherwise have been very difficult to collect (e.g. in private gardens). You can gain access to localized knowledge (e.g. access to certain citizen communities), allowing you to investigate a topic more deeply.

- More innovative research: By democratizing science processes and diversifying actors in the research, new research methods can arise, research strategies can be improved, and new discoveries can be made. This can lead to the production of new scientific knowledge and more innovative, or creative research.

On a broader societal level, citizen science can yield the following benefits:

- More societally relevant research: By including citizens in science, the research can better account for citizens’ needs. New research questions can be identified that otherwise would have been neglected. This can ensure that the research is more societally relevant and publicly accepted.

- Bridging the gap between reseearchers and citizens: Citizen science equals collaboration. When citizens are involved in science, better mutual understanding can be created between citizens and researchers. Overall, this can develop mutual trust and confidence between scientists and the public.

- Diversity in science: When engaging with different actors (inter- or transdisciplinary), more diverse viewpoints and expertise can be included in the research process. This can lead towards more balanced points of view.

Benefits for society

Citizen science can also yield individual benefits and outcomes for citizens in the following ways:

- Scientific literacy: By participating in science activities, citizens can become more scientifically literate16. They gain insights into science in general, with the opportunity to learn specific skills and abilities (e.g. critical thinking skills, understanding basic analytical measurements, etc.).

- Topical knowledge: Being involved in citizen science activities can not only increase knowledge about science in general, but also about the research topic at hand. Through training and experiential learning, citizen scientists may expand their knowledge of the issue central to the project. This is particularly the case when the project invests in educational efforts.

- Behaviour change: In turn, increased knowledge can lead towards changes in attitudes and behaviours. This is especially true for projects related to environmental topics, whereby an increased awareness and support for certain themes can occur (e.g. air quality, mobility, etc.). Furthermore, such raised awareness is known to correlate with environmental stewardship, meaning citizens might grow a stronger “sense of ownership” for their natural environment and community. This can lead towards environmental activism, whereby citizens are empowered to be active stewards. Alternatively, it can lead towards increased political participation or more healthy behaviours, depending on the topic of your research.

More broadly, citizen science can also generate benefits on the political and environmental level:

- Political benefits: The data collected in citizen science projects can help to inform, decide and follow up on policies, which can make them more societally and politically relevant. Citizen science can thereby provide an evidence base for data-driven policymaking. Moreover, by involving citizens in decision-making processes, such as in the monitoring or evaluation of a policy, it can result in greater acceptance and support for important policy themes. The data gathered in citizen science can eventually also impact on policies and institutions.

- Environmental benefits: Citizen science projects can also lead towards actions for improved environments. For instance, citizen science research can help to identify polluters or exotic threatened species, to monitor biodiversity with specific conservation actions, or to reinforce tougher environmental policies, laws or regulations with evidence based data. Sometimes, citizen science projects also have a cross-over with the implementation of nature-based solutions, e.g. tree planting programmes.

Further reading:

- To gain more insights into the outcomes of your project, you can set up a summative evaluation of the project’s benefits for its participating citizens and society as a whole. For executing this type of evaluation, you can check the following online learning course of the Centre of Social Innovation on the eu-citizen.science platform.

- Understanding what citizens gain from engaging in citizen science can help in recruiting and retaining participants. This article from Fan & Chen (2020) matches motivational theories with benefits of citizen science participation.

- The Cornell Lab of Ornithology has developed different tools for measuring outcomes and evaluating citizen science projects. A specific toolkit is available for measuring citizen outcomes.

- Citizen science can yield many more advantages for citizens at the individual level, such as increased social capital, place-making and self-efficacy.

The citizen science landscape

Citizen science projects can be organised within many scientific branches and disciplines. To showcase the diversity, this chapter describes citizen science practices in the natural sciences, formal sciences, medicine & health, arts & humanities, and the social sciences. Some scientific disciplines already have a long-standing tradition with citizen science, while others are just at the beginning.

Specific case studies are provided in each research field. At the end of the module, a list of additional sources is provided with inspiring examples of citizen science across Europe.

Citizen science in the natural sciences

The natural sciences combine the study of living and non-living systems, with specific disciplines in the physical sciences (e.g. chemistry, astronomy, etc.) and life sciences (e.g. zoology, environmental sciences, etc.). The history of the natural sciences is closely related to citizen science. Many amateur scientists have shaped and grounded the natural sciences by observing environmental phenomena and recording their findings. These amateur scientists outlined the beginnings of the professionalization of science. Through this development, the natural sciences are the most commonly practised scientific discipline in citizen science.

The natural sciences easily lend themselves to citizen science approaches through the usage of sensors and/or by organizing large-scale monitoring campaigns across space and time. These monitoring projects mainly invite citizens to collect data by counting species, such as birds or butterflies. The best-known examples of citizen science in Flanders perform(ed) in the natural sciences are focused on biodiversity (e.g. Mijn Tuinlab), mobility (e.g. Telraam) and air quality (e.g. Curious Noses).

The data collected in these citizen science projects can have a significant potential to support public authorities in policymaking. In support of this, the European Commission is advocating a more systematic integration of citizen science into environment-related policy (e.g. the European Green Deal and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals). In this report you can read more about the opportunities and benefits of using citizen science for environmental monitoring, with good practices and obstacles for further uptake.

Case study Animals in the wild – looking for tracks in the city

Green and open spaces play an important role in the quality of life in cities. With increasing population density in cities, these areas and the habitats for urban wildlife are increasingly coming under pressure. Through the project “StadtWildTiere” in Germany, Switzerland and Austria, residents from urban areas are asked to share observations via photographic material of animals or their tracks on an online platform. Volunteers can also rent a camera trap to make observations. StadtWildTiere works with ambassadors, where each ambassador is responsible for observations of one square kilometre of the city. The ambassadors are asked to take regular walks and to talk to residents of their area. A specific training to recognize animal tracks is offered by the institute StadtNatur.

The data are used for scientific studies by a team of biologists and ecologists from the StadtNatur team. Read more about this project: https://stadtwildtiere.ch/

Citizen science in the formal sciences

In contrast to the natural sciences, the formal sciences do not have a long-standing tradition of collaborating with citizen scientists. Formal science is a branch of science studying disciplines concerned with formal systems such as logic, mathematics, computer science, artificial intelligence (AI), game theory, etc. The adoption of citizen science approaches into this field is just in its infancy, but it is expected that new technological developments, especially in the field of AI, will provide momentum.

Examples of mathematical projects that have adopted aspects of citizen science can be found in collective problem solving and distributed computing. Projects in collective problem-solving focus on online collaboration between mathematicians to solve difficult mathematical problems (e.g. the Polymath project), while the latter projects engage citizens who offer their time and devices. Citizen scientists are requested to install and download a tool on their computer. The application monitors the computer for spare computing power and that power is used to solve a mathematical problem. This type of project does not involve the citizens on a personal level, as they only need to install a programme and donate their CPU time (e.g. The Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search).

The usage of AI in citizen science enables cross-over with other scientific disciplines, with citizen science applications using machine learning techniques for biodiversity monitoring for instance. AI is currently used in citizen science to assist or replace humans in completing tasks (e.g. classifying images for species detection), influencing human behaviour (e.g. through personalization and behavioural segmentation), and for improved insights (e.g. training of algorithms using citizen science data). It is likely that new applications of AI in citizen science will appear in the future.

Case study Eye For Diabetes

Citizen scientists in the Eye For Diabetes project examine the retinal images of diabetes patients online via the Zooniverse platform. They mark signs of diabetic retinopathy on retinal images, a disorder which can lead to blindness. The catalogue of images can then be used to teach an algorithm to recognise the disorder, paving the way for screening by artificial intelligence. As such, the citizen scientists are helping to build a reference database of annotated images, which can be used to train an AI software to recognise diabetic retinopathy in future. This project exemplifies the cross-over between the formal sciences and health research.

More information about this project: https://www.oogvoordiabetes.be/

Citizen science in medicine & health

Health science has lagged far behind in adopting a citizen-based approach, although the number of projects in this domain is increasing nowadays. This increased interest is fed by various trends, including increased health literacy among the general population and the emergence of sensors and self-tracking devices. Citizen science in health, or citizen health science, focuses on questions raised by citizens with varying levels of scientific participation with scientists. Often citizens collect data on their own health and act of their own accord to change outcomes.

The development of citizen health science faces certain challenges related to leadership norms. Traditionally, health science and medicine have been in the hands of a few, while participatory science in health comes with shared initiation and leadership. Furthermore, there can be potential liabilities, such as inherent biases that one carries in relation to one’s own interests, challenges and choices or issues with validity of the results. Despite these concerns, there is also a great potential for innovation. Citizen science in healthcare can ensure that the research is better tailored to what patients want, resulting in a higher probability of relevant scientific knowledge for a broader range of stakeholders.

If you are interested in citizen health science, there is an ECSA working group called ‘Citizen Science 4 Health’. Its main objectives are to create a community of stakeholders on citizen science for health, to develop and disseminate tools, methods, ethical frameworks and training material, and to enhance the visibility and potential of citizen science in the health domain.

Case study: Isala

Isala is a citizen science project that wants to get a better understanding of the female microbiome using state-of the-art DNA technology. The project is organised by an interdisciplinary team of researchers at the University of Antwerp. In March 2020, a call was launched in Belgium to f ind 200 people willing to take a swab from their vaginas, skin and saliva. In total, more than 3,300 women reacted and received a testing kit. With the help of bioinformatics, researchers studied the genetic code of the bacteria.

Results revealed that 80% of the participants had a vaginal microbiome dominated by lactic acid bacteria; these bacteria are associated with a healthy vagina. The participants received the outcomes of the study and are further invited for a second phase whereby the research data will be combined with extensive questionnaires to exert factors that impact the health of the vagina.

Read more about this project: https://isala.be/

Citizen science in arts & humanities

Citizen science in the humanities, or citizen humanities, encompasses fields such as languages, literature, history, philosophy and art. The primary object of investigation is human culture, and it favours methods of interpretation, critical thinking and analysis29. Typologies in the citizen humanities range from on-site projects to digital-only projects, whereby citizens are invited to participate in data collection or data analysis of artefacts.

These artefacts can be physical or digital, either collected or provided by archives, repositories, galleries or museums, or provided by the citizens themselves. Citizens often perform tasks that include curating, transcribing, or annotating artefacts. Many projects have been taking place in the arts and humanities. They are often coordinated by universities, museums and archives. In terms of science communication, museums and archives are increasingly incorporating experimental zones and labs, where volunteers can participate or contribute to exhibitions.

If you are interested in citizen science in the arts and https://www.doedat.be/project/index/7796245?lang=en_UShumanities, you can have a further look at this training module of the Parthenos project. It helps you recognize and define approaches for incorporating citizen science into your research project.

Case study:

Enrich your view of Bruges In the citizen science project ‘Verrijk de kijk op Brugge’ (Enrich your view of Bruges), participants help to describe images from the city archives, the public library and ‘Musea Brugge’. Participants are asked to look at the images and describe what they see. Which people can you identify? What buildings do you recognize? Do you recognize Bruges or a borough? Participants complete an instructional form and then transmit the information to the registrars. The finalized information is shared through this website.

Citizen science in the social sciences

Citizen science in the social sciences, or citizen social science, has been developing in meaning and prevalence over the past decade. Broadly, we define citizen social science as an approach that involves participants in a social sciences research project30, whereby they implement tasks which are traditionally implemented by scientists. These projects have a specific focus on social or behavioural aspects, or they take place within an interdisciplinary synergy (e.g. natural sciences and social sciences). A synergy with the social sciences helps to understand the human dimension in the study, enriches the scientific research and helps to boost public participation.

A crucial distinction should be made between citizen social science and the participation of volunteers in a research study by giving an interview, joining a focus group or responding to a survey. These latter are not referred to as citizen science as citizens are the research object and are not actively participating in the research process. Within citizen social science, participants enrich the research process by asking questions or choosing research methods that might not have occurred to professional scientists. Furthermore, they can make the research study more refreshing and inclusive by drawing on their social and cultural capital. Citizen social scientists might have connections with relevant communities or places of interest, which professional scientists might not have considered or have access to.

If you are interested in citizen social science, the CoACT project looks into participatory research forms which are directly driven by citizens and their social concerns.

Case study: Health connects Amsterdam-Slotermeer

In 2014 and 2015, a group of Slotermeer residents attended a training to become Health Ambassadors. These residents interviewed their neighbours about how healthy they think Slotermeer is in terms of litter, exercise and sports, child friendliness, greenery in the neighbourhood, ambience, traffic and transportation, etc. They collected this information from local residents and, in turn, gave them advice on certain topics, such as moisture problems at home. The ambassadors learned how to interview, gained additional knowledge, and started to think more positively about the health of Slotermeer. Moreover, the interviewers came into contact with people outside their direct network. This way, talking about health served a connecting function, crossing cultural differences. The results were presented during a health festival for local residents and other interested parties. They will also be used to complement existing scientific insights and to better align policy with practice. A total of 221 interviews were conducted by 22 ambassadors.

Read more about this project:

http://www.kijkeengezondewijk.nl

https://www.rivm.nl/ gezonde-leefomgeving/kijk-gezonde-wijk-watsap-project

User Type

- Researcher/research institution

Resource type

- Case studies

- Getting started

Research Field